A colonial time-warp from the pages of a García Marquez novel

‘So the Dominicans used to fight with the Jesuits who would clash with the Augustinians?’ asks my friend.

‘No, not the clergy,’ replies our guide, Gonzalo, in Spanish, ‘but rather their supporters would fight amongst themselves.’

‘Like football hooligans nowadays’, I chime in.

‘Exacto!’ beams Gonzalo, ‘I’ll use that analogy next time.’

We exit the dusty Santo Domingo church, mount our bikes and push on as the equatorial sun blazes down. Heat radiates up from the road like standing over a hot stove.

Gonzalo, leisurely pedalling along, yells over his shoulder with a cheeky grin, ‘And now, to the cemetery which hosts some of the town’s most valuable real estate!’

We dismount at the cemetery entrance near a group of elderly men, as Gonzalo begins his next story. ‘During Semana Santa, the town residents dress up and gather in this cemetery to light candles in honour of their deceased loved ones,’ the group of men nod, confirming, as Gonzalo continues. ‘The cemetery is so popular that some Momposinos can’t wait to die—just to be buried here!’

The men cackle with laughter like husky-voiced geese and chime in with agreement.

‘¿Si o no, caballeros?’ Gonzalo confirms with them. ‘Am I right, gentlemen?’

They all nod, still chuckling as one replies: ‘Así es.’

Mompox Cemetery. Lachlan Page ©

We are on a historic bike tour in Santa Cruz de Mompox (sometimes written as Mompos), a UNESCO World Heritage listed town on an island amidst Colombia’s Magdalena river founded in 1537. The once thriving trading post connected the coast with the Andes and was also used as a safe haven if Cartagena were to fall to the British or be ransacked by pirates.

It’s this strategic location that brought merchants, metalwork artisans, the odd botanist—Alexander von Humboldt passed through here—and the Dominican, Jesuit, Augustinian and Franciscan orders who established the town’s churches. This wealth and isolation led Mompox to play an important part in the liberation of the northern part of South America and self-declaring independence from the Spanish on August 6, 1811.

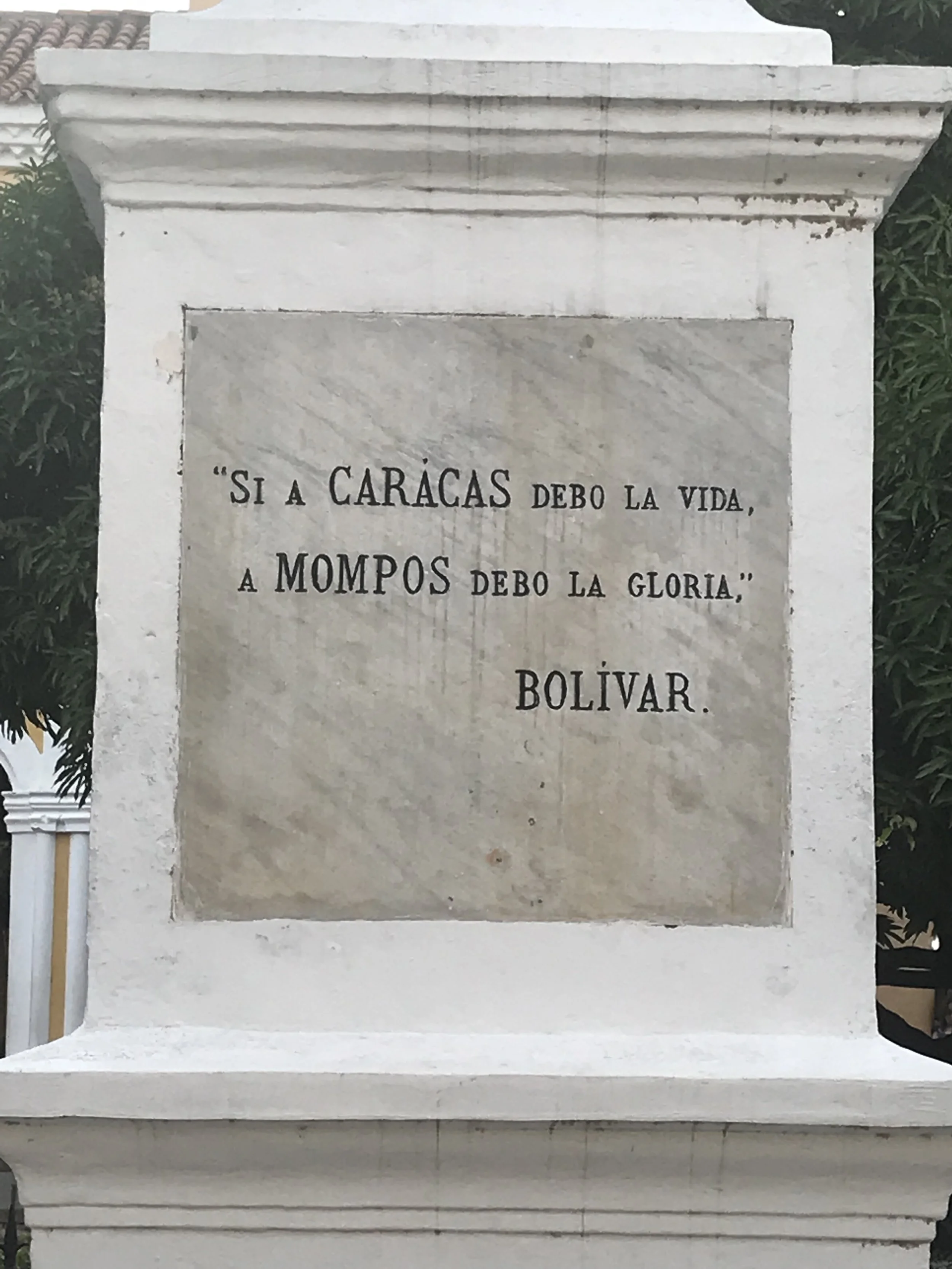

To explore this history further, Gonzalo takes us to La Piedra de Bolívar, a stone which shows the arrivals and departures of Simon Bolívar—El Libertador—who liberated much of northern South America. The stone shows Bolíar passed through here eight times during his independence campaign. On one occasion taking 400 able-bodied Momposino men to liberate his native Caracas, now immortalised in Mompox’s Plaza de la Libertad where Bolivar’s famous quote adorns a statue at its centre. “If to Caracas I owe my life, then to Mompox I owe my glory”. Those with an acute historical eye will also notice the ‘Aqui habito Bolivar varias veces’ signs (Bolivar stayed here various times) around town.

Simon Bolīvar in Casa de la Cultura in Mompox. Lachlan Page ©

Mompox’s Plaza de la Libertad. Lachlan Page ©

After our independence interlude we visit the San Agustin church which holds a decadent, gold leafed religious float, made in France and financed by wealthy local families. Hooded nazarenos carry the float taking two steps forward and one step back following in the footsteps of Christ en route to the church of San Francisco during Semana Santa — Holy Week or Easter. The solemn processions here are some of the most famous in Colombia and are accompanied by candle-holding worshippers and brass music similar to the traditional Easter processions of Seville.

The altar in San Agustin church, Mompox. Lachlan Page ©

Our tour continues on our pious equivalent of a pub crawl as we visit the churches San Francisco, Conception, and finally, Santa Barbara. It’s here, we climb the famous bell tower for a view over the Andalusian-style terracotta roofs and church cupolas where you get a sense that not much has changed since Mompox’s heyday as the once prosperous trading town.

View from the bell tower in Santa Barbara church. Lachlan Page ©

However, while Mompox hasn’t changed, the rest of Colombia has. In the 19th century, a buildup of sediment at a bend in the river nearby made it less desirable and a new port at Magangue was established. Gone are the larger barges and paddle steamers which brought people and prosperity, although it is still possible to arrive via ferry from the port of Magangue. Nevertheless, Mompox remains relatively undiscovered, even for many Colombians.

After our bike tour, we stroll along the Albacarrada (the main promenade along the river) past whitewashed colonial mansions, now housing cafes, restaurants and boutique hotels. We stop to drink icy pineapple juice and watch dugout canoes—similar to the indigenous champanes which feature on the towns coat of arms—ferry school children across the river and fisherman ply their trade on this fast flowing river outlet of the Magdalena.

Refreshed from the arctic jugo de piña, we head away from the river to Calle Real del Medio (Royal Middle Street) — the old part of Mompox consists of three streets parallel to the river: La Albarrada, Calle Real del Medio and Calle de Atrás — to the restored colonial casa which houses Café Ambrosia. We sit down to lunch of fried boca chico river fish, squashed plantain known as patacon, coconut rice and cold local corozo juice.

To beat the afternoon heat, we return to our hotel, La Casa Amarilla, for a much needed siesta. Lying in hammocks around a leafy courtyard, a slight breeze breaks up the dense, humid afternoon air. Rested, we head out at sunset to wander the streets as ornate street lanterns begin to cast a soft glow on the white-washed stucco walls and the crackling hum of cicadas fills the night air. Locals drag their rocking chairs to the street to catch the evening breeze and chit-chat with passing friends. We continue along the Albarrada until we reach El Fuerte, a wood-oven pizzeria housed in the former San Anselmo Fort where the artistic furniture adds to the atmosphere and is, surprisingly, for sale.

During the several days we spend in Mompox, we also take a boat trip to the Pijino wetlands which team with great blue herons and kingfishers while howler monkeys rumble through the treetops lining the river. Back in town, we visit a filigree metal workshop, an ancient, intricate trade weaving together fine strands of gold and silver to create unique jewellery famous throughout Colombia. A technique that remains from its days as a trading port in which gold, silver and emeralds passed through between the Andes and the Caribbean.

Filigree metalwork in Mompox. Lachlan Page ©

Mompox from the river. Lachlan Page ©

However, the real appeal of Mompox is the sleepy, laid back town feel oozing faded colonial beauty and an alluring, lost-in-time charm. You can’t help but think you’re stuck in a time warp wandering the streets past palatial riverside mansions while iguanas scurry along the river bank as the Magdalena slowly drifts past. A far cry from its larger colonial sister, Cartagena, which receives floating cities full of bumbag-wearing tourists daily.

Santa Barbara church. Lachlan Page ©

Colombian Nobel Laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez mentions this magical, isolated charm in his book, The General in his Labyrinth, when General Bolívar comments to José Palacios, his aide-de-camp: "Mompox does not exist. Sometimes we dream about it, but it does not exist."

With a bridge constructed and tourism rising in Colombia, it won’t be long before more people will realise that Mompox really does it exist. Then, those that make the journey and visit her churches can reply as José Palacios did to General Bolívar when told that Mompox does not exist: “at least I can testify to the existence of the Santa Barbara Tower".

How to get there

Mompox can be reached via Valledupar or Sincelejo — hotels can arrange transfers from these locations.

Places to stay

La Casa Amarilla (Carrera 1 # 13-59) Expat run hotel with leafy interior courtyard near Santa Barbara church.

Hotel San Rafael (Albarrada de, Cra. 1 #14 - 57) A 17th Century renovated colonial house offering spacious rooms and a swimming pool, right on the Albarrada.

Hostal Dona Manuela (Calle Real del Medio #17-41) Heritage listed colonial hotel built around an enormous tree with a swimming pool.

Eating

Ambrosía (Calle 19 #1a - 59 | Parque de la libertad) Chic restaurant housed in colonial casa on Parque de la Libertad.

Comedor Costeño (Calle de la Albarrada #18-45) Rustic riverside cafe with cheap local fare (try the Mojarra Frita) and ice cold cerveza.

El Fuerte (Calle de la Albarrada #163 — cerca a la Iglesia Santa Barbara) Austrian-Colombian run wood-oven pizza and pasta restaurant on the edge of town with wooden artwork furniture.